The Chinese metropolis became a ghost town, with food coming in the form of government drop-offs of vegetables and meat, bulk-buying with neighbours in WeChat groups, and online grocery shopping.

Because the government distributed food based on housing unit, not occupancy – meaning a household of five would get the same amount of food as a household of one – many residents had to turn to the latter two options.

But for those less tech-savvy, particularly the elderly, such choices were out of reach.

Even though Ke lived alone, she had to carefully calculate and plan how much food to eat every day. She could not help but wonder how the elderly managed to secure enough food using mobile phones.

Her solitary confinement turned her initial acceptance of the situation into a full-blown panic.

On May 1, 2022, she got a phone call from her mother, who urged Ke to leave and go take a master’s degree in a new country, where she could start over.

I was deeply attached to Shanghai, but the reality hit me. I had to go

Claudia Ke, a 35-year-old woman who left China to study in France

At first, Ke had no interest in leaving China, Shanghai or her friends. Besides, the process of emigrating to a Western country such as the United States, Britain, Canada or Australia could take significant time for a Chinese citizen, and required a sizeable investment.

But her growing distress over the lockdown, the cabin fever and seeing authorities in hazmat suits kicking in peoples’ doors wore her down.

By the time Shanghai lifted the lockdown mandate that June, she had convinced herself she could do better elsewhere and began preparing to leave.

“I spent 10 days considering whether to leave,” says Ke. “I was deeply attached to Shanghai, but the reality hit me. I had to go.”

A month later, she was back with her mother in her birthplace, Beijing, and began submitting school applications across Europe.

She was accepted as an MBA student at the Burgundy School of Business and in the summer of 2023, before leaving for France, she sold her consulting company.

Ke is one of many Chinese women in their thirties who have decided to pursue an overseas postgraduate degree.

Multiple factors fuel their decision, including the deep-rooted stigma of being an unmarried woman at that age; dashed career hopes resulting from China’s poor post-pandemic economy; tightening political controls that are seen as having taken away even more freedom; and gender discrimination and ageism in the workplace.

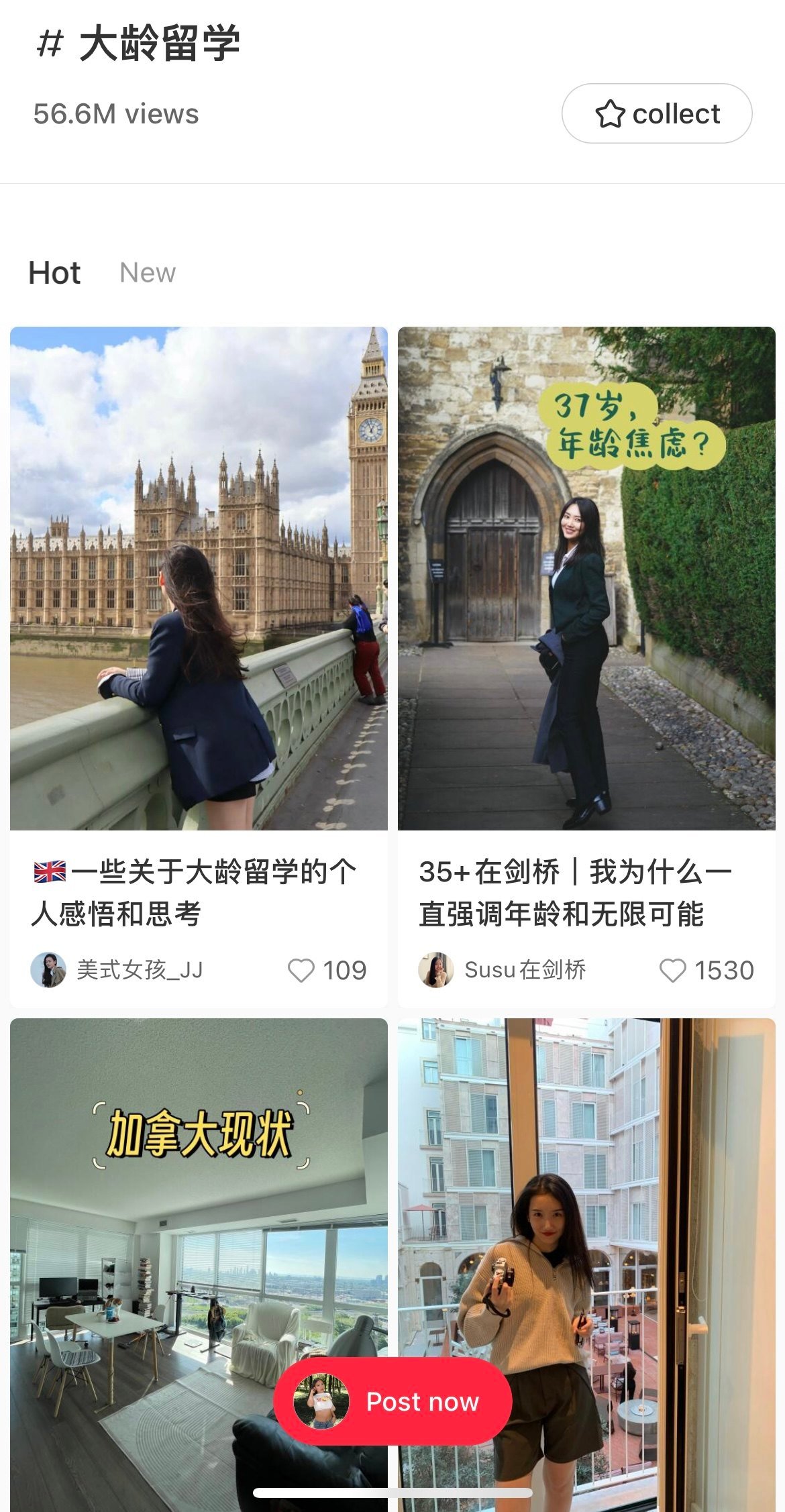

On Chinese social media site Xiaohongshu, the topic da ling liu xue (“studying abroad at an older age”) is being feverishly discussed, with the related hashtag generating more than 56 million views.

“Older Chinese women try to flee the country through higher education overseas even if they don’t have a clear idea of what the future holds in a foreign country,” says Ke, who offers educational consulting sessions for women following a similar path to hers.

Since May last year, she has received more than 2,000 private messages on social media from women seeking advice on selecting programmes and applying for schools.

This increasingly popular trend among Chinese women is part of a larger “run philosophy”, or run xue, a buzzword coined during the pandemic meaning “the study of running away” and expressing the desire to escape China.

According to data provided by WeChat, searches for “emigration” reached 33 million in 2022 – a roughly fivefold increase from 2021. WeChat later censored search data for this specific term.

But women like Ke are not convinced.

It ignited anger on social media and sparked an online movement seeking justice, with many wanting to know who the woman was, why she had been chained and under what circumstances had she given birth to eight children.

Douyin swiftly took down the account that originally posted the video, while Weibo censored related hashtags and posts. Meanwhile, in the media, the focus of the incident was shifted to the woman’s mental health.

The attack left two women needing admission to hospital and stirred outrage over sexual harassment and gender-based violence. State media, however, steered the narrative from gender to gang violence.

Thirty-year-old Carrie Cai, from Chengdu, in Sichuan province, had long endured criticism from relatives for not getting married. So after the pandemic, and seeing little hope in China’s economy, she decided to seek a better future in Ireland, where she spent her savings on a master’s degree programme in computer science.

Her research suggested Ireland had more lenient policies for permanent residence than other English-speaking Western countries.

When she landed, in the summer of 2023, she was overcome with excitement. But returning to school at 30 was not easy.

It’s a more radical move for Chinese women over 30 to study abroad because they’re already rejecting the standard script

Carrie Cai, a 30-year-old Chinese woman living in Ireland

Unable to understand and absorb obscure mathematics concepts during lectures, she sought additional help from tutorials on YouTube and Bilibili. “Even if I were taught in Mandarin, I wouldn’t understand,” Cai laughs.

To her parents, discarding a stable career for an uncertain future was irresponsible and unwise. Cai’s mother had asked: “Why can’t you follow the mainstream? People your age get married and have babies. This is a societal rule.”

Despite her parents’ disapproval, study stress and far harsher weather than she was used to, Cai stuck to her resolve. And while studying, she met other “older” Chinese women who, like her, were dissatisfied with China’s working and living environment.

She also discovered that Ireland’s Employment Equality Act prohibits discrimination at work on the grounds of age, race and gender, that there were companies that hired more women than men, and that some careers fairs were designed specifically for women.

In Chengdu, Cai had worked in the operations department of a tech company, which had offered a stable pay cheque but little room to grow. An avid reader of feminist literature, she embraced life as an independent woman who valued personal development over marriage.

She understood the impracticality of switching career paths after 30 and that employers would see the possibility of pregnancy and child-bearing as an economic risk.

According to a 2023 report by recruitment site Zhipin.com, 61.1 per cent of women in China were asked about their marital and pregnancy status while applying for jobs, and 51.1 per cent believed age affected their career prospects.

“Women going abroad to study is a strategic response to bias in the labour market,” says Fran Martin, an associate professor in cultural studies at the University of Melbourne, who spent five years researching the lives of Chinese women students overseas.

Why would I follow the mainstream by settling down and being a mum?

Carrie Cai

“Escaping” is also a way for women to deal with a contradiction in Chinese society: women born under China’s one-child policy were raised to be self-motivated, pushed forward in education, and encouraged to have careers and think of themselves as important.

“It’s a more radical move for Chinese women over 30 to study abroad because they’re already rejecting the standard script,” says Martin.

While Cai’s parents and relatives doubted her choice, her female friends showed tremendous support. Inspired by her, one of her friends plans on going overseas for a master’s degree in five years.

Many of Cai’s classmates are younger Chinese students, but they are a completely different group in their attitude, she says. “Younger students would complain about how boring this place is. There is no good food, no entertainment. But to us, we’re not here to be entertained.”

In January, Cai received her first exam results. She had been worried because failing just one class would result in expulsion. Her heart raced as she clicked on the link to her grades.

“I passed!” she screamed. Her hard work was paying off. The one-year programme will end in five months, and finding a job to stay in Ireland has become a priority.

“Why would I follow the mainstream by settling down and being a mum?” she says. “Why couldn’t I take control and live a different life? You only live once.”